Over the course of human history, most people who have ever lived… lived outside.

Before I continue, I want to name a tension here. For a couple paragraphs, it’s going to sound like I’m glamorizing homelessness: saying it’s not that bad, that it’s acceptable, or even normal. If you read to the end, you’ll see that I am unequivocally not saying that. So hang tight, and trust me for a bit.

Since relocating to Minneapolis from LA, I get a lot of questions about how unsheltered people survive the colder weather. In cities that endure multiple months of below freezing temperature and deep snow, many choose to retreat temporarily to shelter, as more beds open to accommodate (though rarely does the supply meet the demand, in quantity or quality.) But a great many remain outside, either by choice or the lack of capacity or access to shelter. There are always great losses, and a great many who endure.

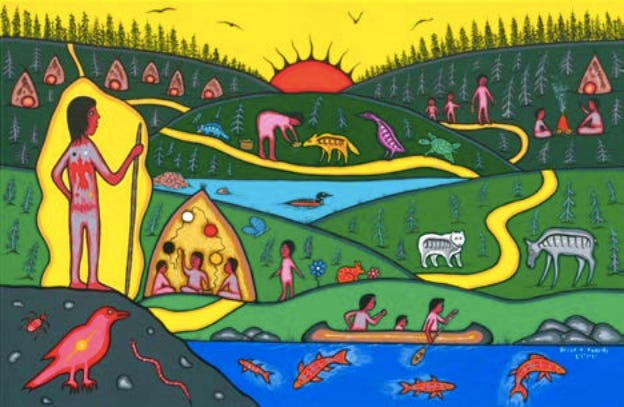

In all this, an important truth to bear in mind is this: people have inhabited cold terrains like Minneapolis for thousands of years—in structures similar to the tents that unhoused people inhabit today—long before the advent of dual-paned windows, drywall insulation, or indoor heating.

So what’s different now?

Certainly some good things have come along that have improved the standard of living. Houses, electricity, refrigeration… things that make us less vulnerable to the temperamental elements. A key difference, then, is that some have the ability to not have to live outside.

But we delude ourselves if we believe that’s the only thing that’s changed. The way we relate to people who live outside is fundamentally different now than when it was the norm. Here’s a few example (though this list could be its own essay):

Access to the natural resources of the land (food, water, naturally-occurring shelter) was once open to all, and is now seized and privatized.

Groups were able to form rooted communities with traditions and celebrations and a connectedness to place, but are now criminalized, segregated to uninhabitable places, and frequently forcibly relocated.

Individual and communal survival were more deeply linked, necessitating solidarity and shared care, but we are now taught that we are each only responsible for ourselves.

I’m not suggesting that we can or should return to a pre-industrialized society as though that’s the pinnacle of human existence. I am pointing out, though, that the fundamental issue with homelessness today is not that people live outside: it’s that we created a society exclusively for people who live inside, and then cast large swaths of people out of it. We seized control of a river meant to nourish everyone and are selling it back to people, leaving some without access and calling it “the way the world works.” (This was meant to be a metaphor, but we also literally do this.)

And this gets to the core of why I’m so defensive of encampments and their right to exist and flourish in the midst of our generations-long housing crisis. All of what we consider to be “advances” in society could have been for everyone, and yet in the West we have largely decided that allowing some to profit from progress was more important than everyone flourishing together.

When we do this with housing, encampments form—in a way, returning to a more human way of living that prioritizes interdependence and shared survival. So we punish them for it—in part, I believe, because it shames us; it exposes some of the central lies we used to prioritize progress over beloved community.

But the truth is that we could have both. There is enough! Everyone could eat, have access to water, health care, internet, even air conditioning. We could have all those things and enjoy communal care, solidarity, and flourishing. We just choose not to.

And until we make a new choice, unsheltered people will bear the consequences. Every Winter, we lose hundreds of our neighbors.

The next move is ours.

These posts will always be free.

But the rest of my work—traveling to speak and lead workshops, creating content, advocacy and direct aid—is enabled and expanded by your support. Consider becoming a Paid subscriber to enhance my reach.

two things: 1. I think it is important to stop having such a rigid idea of thinking of homeless people as different than housed people. I have gone to church since I was born. The second I ran out of unemployment unexpectedly and ended up in a homeless shelter, people treated me completely differently I knew and slandered me for years to the point I could not start over at a new church without people introducing me as - hi this is Naomi, did you know she is poor lets be nice to her because she is poor( after I was no longer homeless) All I wanted was life to be normal again. 2. part of the reason people sleep outside is because we have 3 month and month long stays at shelters and 3 year waits for housing... for example. and Churches need to stop thinking of shelters as a solution to homelessness and preventing homelessness as a solution. I volunteered for years in Flagstaff AZ at church and I only needed help for one month on a 2 month lease and instead of being willing to help me with one month of rent they thought an eviction on my record and living in the local temporary homeless shelter would solve a problem. People I volunteered there with who live in Minneapolis thought it was so nice to romanticize the shelter. If I did not get evicted I would probably been able to avoid any long term homeless situation. Also, homeless people who take the bus do not get more used to it than people who have a car. I had one pastors wife assume I was a different kind of a human being who must have adapted in a way she could not since she was not poor. Money does not make people a different species.

"So we punish them for it—in part, I believe, because it shames us; it exposes some of the central lies we used to prioritize progress over beloved community"

my jaw dropped at this!!!!!!